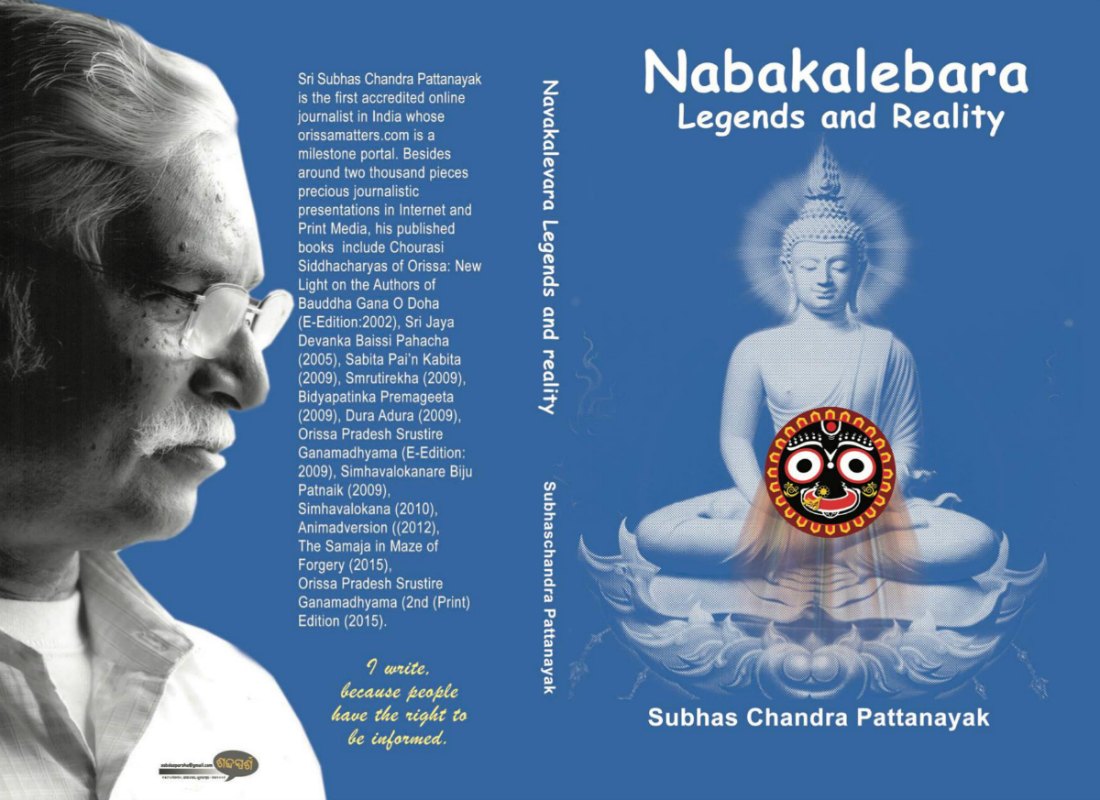

In this era of two-minute research noodles made viral through smart memes and quick tweety wits, Subhas Chandra Pattanayak’s “Nabakalebara: Legends and Reality“ (Shabdasparsha, 2015) is not one that everyone would probably want to read. I will not therefore pitch it as a bestseller on any list since most indulgences these days target individuals, not ideas; offer quick fixes to assuage hurt egos, not undergo painful process of seeking new knowledge. So much so that words like enlightenment and intellectualism are downrightly condemned, matter-of-factly in our times. But suffice it to say that any serious reader of anti-caste history and of Indian atheism will find this book invaluable, if not the most valuable reference – not just as a scholarly research material to take a radical departure from credentialed academic works, but more importantly as a weapon of social justice against the remnants of regressive tendencies in our present world.

Throughout the pages, this book makes no pretensions and it spares none from critical reappraisals. It takes on the mighty and the powerful hegemonic interpretations of Buddhism – from Sankaracharyas to Dalai Lamas, from Upanishads to Asokan inscriptions. Most importantly, the book destroys the myths concocted by Brahminism to hijack Jagannatha from the indigenous cultural mores to confine subsequently within a Hindu temple walls.

Using vast primary research materials and original interpretations with unprecedented scholarship in modern Indian history, this is a book that ably argues against most conventional givens in our historical readings into origin and scope of Buddhism. The author makes the claim that “Emperor Asoka’s attack on Kalinga was meant to obliterate Buddha as the God of the Oriya tribes and to desecrate his sacred birthplace near Dhauli Giri so that the fountainhead of Buddhism would dry out.” Asoka, he writes, had attacked Orissa in order to promulgate autocratic rule in obliteration of tribal democracies and to establish the hegemony of Brahmins, as contemplated by Chanakya, over the society for which it was necessary to eliminate Buddha’s birthplace.

Pattanayak says Buddha’s Sangha was based on Chanda – the first system of voting in the world, which in turn is used variously in Orissa – Chandaa (donation), Chandaka (Buddha’s horse), Chandaka (forest area during Buddha’s era in Toshala region). Bundles of Kau’nria Kathi used for “fire salute” by the Oriyas are likewise symbolic of the strength of unity which their ancestors had shown against Aryan aggressors in the Kalinga war.

The author details how Budhha was against caste system, how Tantra has no caste consideration and how Mother Kali targets adherers to Brahminism. Therefore, Sankaracharya’s sole aim was to promulgate Brahmanya Dharma against Jagannatha (who is worshipped as Kali and as Buddha in Orissa).

The reason why there is no “Badabadua” (who is Buddha, according to the author) in Brahmin families is precisely because it is unique to the Buddhist matriarchal heritage. The significance of it amplifies with his research asserting that Buddha was born in Kapilavastu of Orissa (Kapilavastu literally meaning reddish soil). Badabadua likewise is made of reddish soil and if reddish soil is not available in their own area, non-brahmin Oriya families have imported it from wherever it was available. “It is significant that Badabadua – the most important deity of the Household – is not to be found in Thakura Ghara (a room dedicated to deities accepted and worshiped by Brahmins). It is established in the secret Aisanya Kona of the Handishala and worshiped secretly by the GruhaKarttri (reigning lady of the family). The first handful of cooked rice is offered to Badabadua by the house lady in the Handishala itself,” Pattanayak writes. Badabadua is Buddha and Buddha is SriJagannatha, who is also first offered cooked rice by the woman of the household, as depicted in Indrabhuti’s Vajrayan.

Buddha’s sword “Prabalayudhha” is still being worshipped in Narasinghpur of Orissa as “Prabala Devi”, the eldest member of the royal family is named “Bada Raula”, thus named by Rahula, the son of Buddha. At the worship occasion however, no Brahmin is allowed. “Leave apart worship, even the appearance of the shadow of a Brahmin is also prohibited in this place. This strict prohibition of Brahmins to the Gupta Puja of the Sword of Buddha is indicative only of the fact that, knowing the Brahmins’ conspiracy against Buddhism, Oriya tribes were keeping them away from intimate worship of Buddha.”

Similarly, an egalitarian festival that is prominently celebrated across Orissa except among the Brahmin families is “Khudurukuni Osha” – when Oriya girls erect mini Buddha Stupas on the river banks with sand and soil and worship the Sun – which is synonymous with Mangalaa/Buddha – the idea of Jagannatha’s fertility chapter beginning from Mangalaa therefore. The protagonist of Khudurukuni is Ta’poi whose narrative depicts how the Brahmins were harassing the Buddhist Sadhava families in Orissa. Ta’poi was the only sister of the seven seafaring Sadhavas – eventually saved by Mangalaa, the deity of Orissa’a non-Brahmins, who is worshipped, without the presence of any Brahmin priest.

Likewise “Budha Mangalabara Osha” observed across Orissa in non-Brahmin households equates Buddha with Mangalaa – and the author describes why the women in Orissa also worship Mangalaa on Budhabaar – as Buddha is equated with Budhabaar among the Sabara tribes in Orissa. The story behind this occasion revolves around a Sabara woman’s friendship with the wife of a Sadhava, which gets resolved through Sadhavas worshipping SarvaMangalaa for 13 Buddhabaras (Wednesdays).

The author goes on to describe the cults of Patitapavana (Sudarshana being Dharma Chakra of Buddha and carried only by the non-Brahmin lower caste – “Lenka”) and Coition (the Jagannatha system as a system originally of Bauddha Tantra or cult of coition). Pattanayak writes, “This ‘Cult of Coition’ conceived and espoused by Sahajayan – the refined philosophic metamorphosis of Vajrayan – is the basis on which the concept of Nabakalebar stands. As the time of Nabakalebar arrives, this Vajrakila in form of Sudarsana proceeds in search of the wood and preparation for the new image of SriJagannatha starts with the approval of Mangalaa of Kakatapur.”

Why Kakatpur, why Deuli, who is the “Prakruti”, why a wooden log to create the eternal torso – which the author argues depicts a female are among many questions the scholar probes into. “The eyes of SriJagannatha and the breasts of the woman are strikingly similar. In the torso, the breasts are prominent, in the SriJagannatha, the round eyes.” Only in Jagannatha are the eyes (in mainstream interpretations, “Chaka Aakhi”) placed in human chest – only because they are indeed the breasts, per the author.

He further writes, “Jagantaa-Tha of Orissan Tribes to whom Buddha was their benevolent Lord – full of motherly mercy, responsibility and compassion – metamorphosed into SriJagannatha in the new direction, which Siddha Indrabhuti gave to Buddhism through Vajrayan and its scripture ‘Jnanasiddhi’.”

Why Buddha is god of agro-magic, why Jagannatha is female and why for the Sabara tribe, Raja festival (which is exclusive to Orissa) was a commemoration of earth’s intercourse with the clouds leading to germination of seeds – is another set of questions investigated by this work.

Among literally countless new revelations, the book proves that contrary to Hindu Brahminical scriptures, Jagannatha is no Bishnu, and the “so-called Brahma which is being put into new images of SriJagannatha on the occasion of Nabakalebara is nothing but misnomer.

How did Vedic Hinduism enter Orissa? The author writes, “Condemning matriarch tribes as ‘Mudhamati’ (stupids), Shankara had insisted upon worshiping Govinda, (Bhaja Govindam, Smara Govindam, Gobindam Bhaja, Mudhamate), as the economy of Aryas was fully dependent on cow. King patrons of Brahminism were supporting Sankara and because of that, Vedic Sanatan Dharma had engulfed Orissa. Caste-supremacists were running reign of terror and churning out concocted legends to transform SriJagannatha from Buddha to Vishnu. In this process, Indrabhuti was changed to Indradyumna and lies were created to add strength to this mischief.”

The ruling class was orchestrator of this mischief. “Hindu King Purusottama Dev was a rabid hater of Buddhism and was a great patron of Brahminism. In fact, Brahmins had made him their weapon against real cult of SriJagannatha…. On occupying the throne, Purusottama Dev not only fortified Brahminism with sixteen citadels of power in the Buddhists dominated areas, but also tried to extinguish Buddhist identity of SriJagannatha by transforming the deity of SriMandira to Govinda Krushna.”

Sankaracharya (Adi Sankara and his chela Sankaras called Sankaracharya of Gobarddhan Math of Puri) needed to change Jagannatha from Buddha to Vishnu to revive Sanatan Dharma, says Pattanayak. But this was vehemently opposed by the Oriyas. This book details the series of attempts by the royal class and the confrontations by the masses, almost always through progressive literature.

This book also exposes the vile misogyny that is canonized in Brahminism. Extensively citing scriptures throughout the book, the author rips apart the sacrosanct. The author writes, “Brahminism had no respect for the human rights of women. Rather, it had contrived ways to torture them, so that, they shall permanently stay in a condition of pusillanimity to bear children for them as and when they so desire. In Brhadaranyak Upanisad, under the fourth Brahmana of the sixth chapter, it has called upon to use brutal force on any woman of choice to create panic in her, so that she shall be willing to be raped, because the Arya male has to beget sons through any woman he likes.” As opposed to that, the progressive history is invoked by the author with his authoritative translations of works by the great Sahajia Jaya Deva – born in Orissa – who depicts the woman as the protagonist in lovemaking.

Writing about political economy of male chauvinism in cow-based Vedic society, Pattanayak says, “Vedic male-superiority over women had a hidden evil design. Unless women were suppressed, the Aryan method of caste exploitation that was giving the Brahmins and their allies – the Kshatriyas – the right to luxurious life without any physical labor, had to collapse. Women being the inventors of agriculture and being the paragons of equality at least amongst their respective children, had given birth to tribal democracies based on economy of equality. This is why, the Vedic chauvinists, i.e. the Brahmins were eager to keep the women as inferior beings. They were just tools to beget sons and were domestic helps to work for their husbands and nothing else. Sons were essential for the males in Vedic society to help them acquire property and expand their cattle flocks.”

Far from getting submerged in history alone, the book locates the present administration in Orissa and its role in perpetuating the legends to suit the ruling elites. The recent controversy over the passage of auspicious time for Nabakalebara is needless, according to Pattanayak. That is because, “No Hindu canon applies to SriJagannatha as He is not a Hindu God and the Sabara tribe, whose God is SriJagannatha, has no canon of its own that stipulates a time in the night for the transfer of the secret material by them from the old to the new body.” He reiterates that instead of waiting for the brahmin mafias to determine the scope of damages caused by such negligence, people of Orissa, amply equipped with progressive historiography on Jagannatha should remember, that in anything Buddhist, there is no authority granted to Brahmins, and historically Brahmins are not even supposed to enter the area of Buddhist functions anywhere in the State.

What Do You Think?